Alameda’s Central Avenue Complete Streets Project passed a key milestone in receiving city council approval to move forward into final design. As we’ve previously covered, safety improvements are badly needed along the corridor: it is home to 2,500+ students at several schools, as well as notable destinations such as Webster Street, Washington Park and Crab Cove. The proposed design concept includes a range of safety improvements for all users, including bulbouts and crosswalks, dedicated left turn lanes, a two-way cycle track from Pacific Avenue to Paden Elementary School, and bike lanes along most of the remaining corridor. Notably, the project would create Alameda’s first near-continuous cross-island bikeway by connecting to existing bike lanes east of Sherman Street.

• An extra travel lane (four lanes, instead of three)

• Parking

• Bike lanes

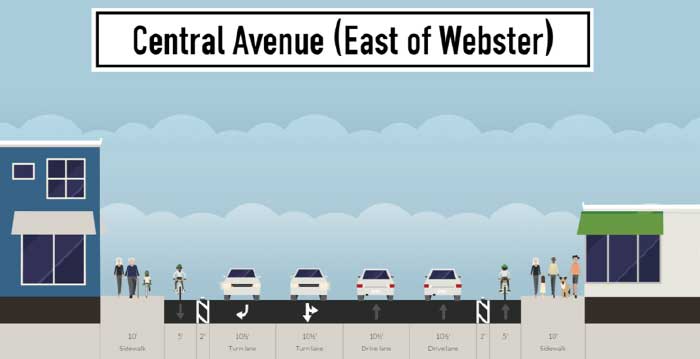

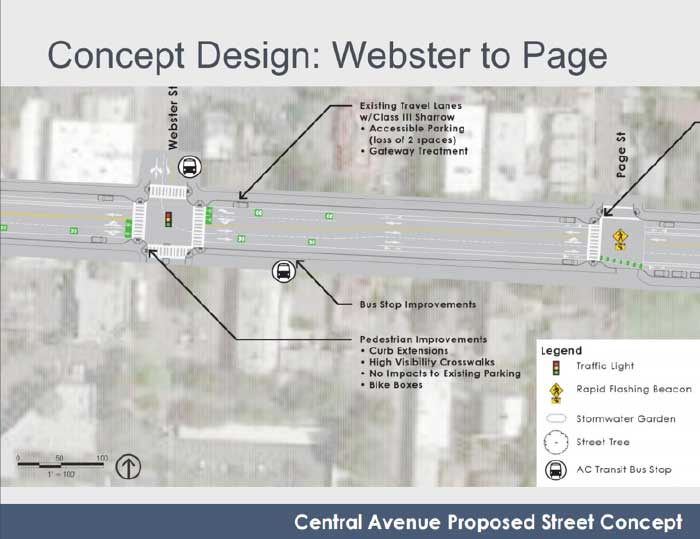

Along most of the corridor, the City has prioritized parking and bike lanes over an extra travel lane, but between Webster and Eighth, the City has prioritized an extra travel lane and parking over bike lanes. What makes this segment tricky is it experiences higher traffic volumes than the rest of the corridor, particularly for vehicles turning right onto Webster and Eighth. The extra lane accommodates these higher right turn volumes, so this choice is understandable.

Conversely, the City’s prioritization of a handful of parking spaces over protected bike lanes offers an opportunity for improvement. The design concept preserves about 20 parking spaces and a commercial loading zone in lieu of bike lanes (about 14 metered spaces near Webster and six unmetered spaces near Eighth). Removing 14 metered spaces serving local businesses may seem like a lot, but nearly every business with frontage along Central contains existing off-street parking totaling over 270 spaces. Continuous, protected bike lanes could therefore be achieved by reducing immediately adjacent parking supply by less than five percent. This tradeoff seems like a no-brainer for businesses: in New York City, installation of protected bike lanes led to a 49 percent increase in retail sales.

• Continuous bike lanes would require modification of pedestrian bulbouts, but much of the same benefit of reducing pedestrian exposure to cars would remain in a protected bike lane configuration.

• Even with protected bike lanes, both intersections present conflicts associated with high right turn volumes. Dedicated bike signals and protected intersection elements could help reduce these conflicts while maintaining separation between people driving and biking.

• Bus stops may present conflicts, but a range of design solutions are available such as the planned design for Oakland’s 20th Street. Given the low bus frequencies at these stops, a shared design wouldn’t be a deal breaker.

The City’s staff should be commended for their delivery of a community-driven design concept along a very challenging and constrained corridor. However, in order to achieve the safest possible design for all users, the City must reassess its priorities for the weakest links at the intersections of Webster and Eighth. It would be a shame to make it this far without closing the final barriers to safe, continuous, low-stress travel for everyone.