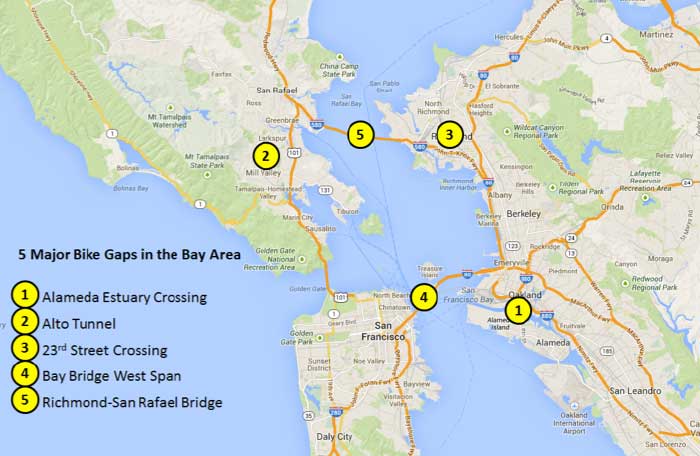

As Bay Area cities redesign their streets to better accommodate safe bicycling, key gaps in the region’s infrastructure become ever more apparent. Much of the growth in bicycling over the past decade has resulted from a number of cost-effective on-street investments — bike lanes, cycle tracks, and bicycle boulevards – and there is still much work to be done in these areas. But it’s also worth taking a step back to look at some of the Bay Area’s biggest gaps in bicycle infrastructure that would require more costly investments.

We’ve put together a list of five major bike gaps in the Bay Area. Some of these gaps are close to being addressed; others remain dreams that are far from becoming a reality. Each project is certainly fun to imagine.

1. Alameda Estuary Crossing

The Posey Tube links Alameda and Oakland

Image: Oakland Tribune

Estimated Cost: $75 Million

Riding a bike from Alameda to Oakland via the Posey Tube is a terrifying experience. The lack of a good bicycle connection is a major missed opportunity: biking is on the rise in both cities, and an alternative to traffic congestion for the Webster/Posey tube is desperately needed. A safe, pleasant bike connection from Alameda to Downtown Oakland and its BART stations could be one of the most heavily used bicycle routes in the Bay Area: if just 5 percent of trips across the 0.2 mile wide estuary occurred by bike, this could amount to 3,500 bike trips per day (for some context, Market Street in San Francisco serves more than 6,000 bike trips per day).

While Caltrans is upgrading the lighting and cleanliness of the Posey Tube, more robust improvements are limited by space constraints. A free shuttle is currently offered between the College of Alameda and Lake Merritt BART/Laney College that accommodates up to ten bicycles, but the shuttle runs infrequently (every 30 minutes) and with limited span (during morning and evening commute hours only).

A bridge for bicyclists and pedestrians could reshape travel options on the corridor. The City of Alameda studied the feasibility of a new bicycle/pedestrian bridge in 2009, but the project appears to be stalled due to funding. Yet, the projected $75 million cost is far from insurmountable given the potential heavy usage, redevelopment of the Alameda Naval Base, and likely multi-billion dollar countywide transportation sales tax initiative in 2016.

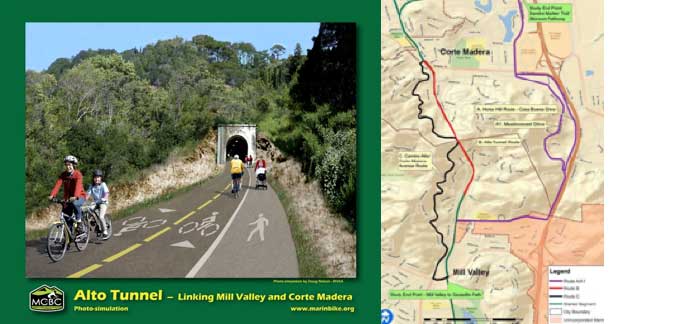

2. Alto Tunnel (Mill Valley/ Corte Madera)

Image: Marin County Bicycle Coalition

Estimated Cost: $40-$50 Million

The 0.4 mile Alto Tunnel between Mill Valley and Corte Madera serves as a critical barrier to biking and walking between Southern and Central Marin. The Alto Tunnel was built in 1884 to serve the former Northwestern Pacific Railroad. The tunnel was closed in 1971 and the southern portal partially collapsed in 1981.

A restoration of the Alto Tunnel would not only expand transportation options between Corte Madera and Mill Valley, it would create a near-continuous “bike highway” from linking San Francisco and Santa Rosa (and beyond) via the soon-to-be-completed SMART bike trail. A 2010 study projects that restoring the Alto Tunnel would serve 2,300-5,000 trips daily. Transportation represents 62 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in Marin, so such a project is much-needed.

Marin County will soon complete property and geotechnical studies for the tunnel. Barring any unforeseen issues, it is expected that the county will continue moving forward with the tunnel restoration. Restoring old rail tunnels for bicyclists and pedestrians is nothing new for Marin County: in 2010, the Cal Park Rail Tunnel reopened linking San Rafael and Larkspur.

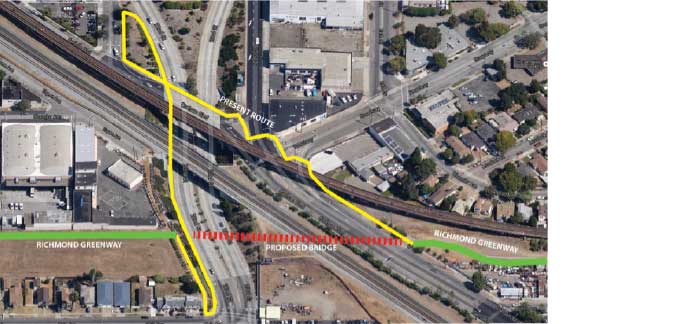

3. 23rd St Crossing – Richmond Greenway

The Richmond Greenway is bisected by 23rd Street, railroad tracks, and Carlson Blvd, requiring a complicated, circuitous detour.

Estimated Cost: $12-15 Million

The Richmond Greenway has been a valuable addition to the City of Richmond since it opened in 2007, but the greenway’s full benefits will not be truly realized until the City bridges the trail’s gap at 23rd Street. Presently, the trail abruptly ends at 23rd without a safe or intuitive crossing: a complicated, circuitous detour is necessary to travel from the greenway’s western half to its eastern half. This detour effectively requires bicyclists to illegally ride on the sidewalk.

Active transportation options are badly needed in Richmond, a city where 58 percent of adults and 52 percent of children are overweight or obese and many people lack access to cars. Bridging this gap on the greenway would reduce the physical isolation of the Iron Triangle district and expand access to schools, jobs, and retail in the area. Additionally, it would create a nearly seamless trail connection from Richmond to Downtown Berkeley (in addition to a gap closure at the Richmond-El Cerrito border). The trail may connect to the Bay Trail in Point Richmond, a new extension to Point Molate, and ultimately across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge (see #5).

A bridge over 23rd Street was identified in the 2003 Richmond Greenway Master Plan (PDF) as part of a future project phase. Assuming typical rates of cost escalation, a bridge would likely cost around $12-$15 million. It is presently unfunded.

4. The Bay Bridge West Span

Image: MTC

Estimated Cost: $500 Million

This list would certainly be incomplete without mentioning the Bay Bridge West Span. A trail on the West Span is the elusive Shangri-La of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure in the Bay Area. It would have huge benefits—given the trip volumes on the corridor, it is easy to envision more than 10,000 daily trips by biking and walking across the west span if a trail was built. But the cost – approximately $500 million – is likely prohibitive. MTC has looked at the project multiple times (PDF, PDF), and it appears that there is no easy solution.

The challenging regional policy question for the Bay Bridge West Span is how to prioritize such a massive investment in relation to relatively lower cost investments that serve more communities and more trips. For example, at roughly the same cost as the Bay Bridge West Span Trail, San Francisco could implement a full build-out of its Bicycle Strategy to capture 20 percent of all city trips by bike—thereby serving many more trips and providing greater environmental and health benefits. The cost-effectiveness of a West Span bike trail unfortunately doesn’t seem to stack up in this regard.

5. Richmond-San Rafael Bridge

Image: Bikesyes.org

Estimated Cost: $55+ Million

Like the Bay Bridge West Span, the 5.5 mile Richmond-San Rafael Bridge has been a high-profile barrier targeted by bicycle advocacy groups for decades, but only recently has the project gained new life. A bicycle and pedestrian path along the unutilized shoulder lane on the upper deck would be primarily used for recreational purposes. Caltrans had rejected multiple trail proposals despite the support of a host of agencies, including the Bay Conservation & Development Commission (BCDC), Bay Area Toll Authority (BATA), Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD), Marin County Board of Supervisors, and Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC). Caltrans’ opposition was not financial – it spent over $1 billion on seismic retrofits in the mid-2000s – but related to its desire to preserve the vehicle capacity for a future widening to three lanes of traffic (even though most traffic congestion is on the lower westbound deck during the PM peak).

However, things are quietly changing. Last month, BATA authorized a comprehensive evaluation of designs for a bike path on the upper deck of the bridge and a peak-hour eastbound auxiliary lane on the lower deck. The study will also include an evaluation of options linking Point Molate with Point Richmond (the terminus of the Bay Trail and Richmond Greenway). Although Caltrans hasn’t yet signed off on the project, BATA offers a specific timeline that indicates the project may be getting serious: if all goes according to plan, construction could begin as soon as 2016.

What major bicycle gaps would you like to see fixed?