Should Downtown Oakland be a great place to drive, or a great place to walk and bike? As Downtown lies on the cusp of rebirth and growth, these divergent transportation visions are taking shape. On the one hand, Oakland strives to be a leader in sustainability, health, and social equity by prioritizing active transportation and multimodal planning. On the other hand, many of the City’s transportation policies still reinforce 1950s-style car-first planning that do not reflect the modern needs of its residents. While the City has pursued several forward-thinking complete streets projects, it is simultaneously implementing projects that make walking and biking more difficult.

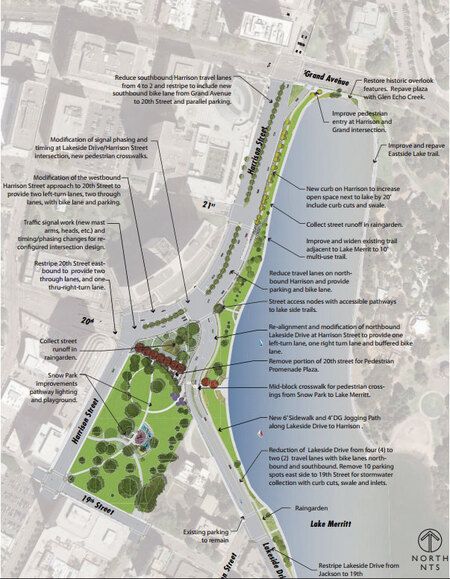

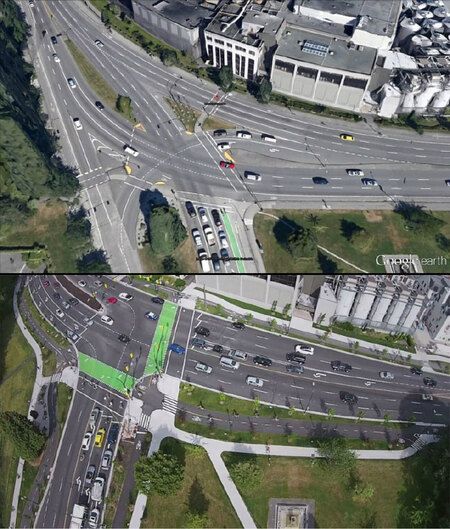

The Lakeside Green Streets project is emblematic of this ongoing struggle to restore Downtown for people while car-first planning still dominates. The project will rebuild a dreadful intersection of Harrison Street, 20th Street, and Lakeside Drive as well as the highway-like eight lane segment of Harrison between 20th and Grand. While the “Green Street” project offers some exciting improvements including a restored waterfront and expanded Snow Park, it maintains a deeply flawed and functionally obsolete highway-like design on Harrison Street that continues to prioritize cars over people.

This post tells the story of a flawed project conceived almost 15 years ago based on antiquated traffic engineering standards and faulty traffic projections. Without the institutional will to update the design, Oakland will spend precious financial resources to reinforce an unsafe barrier to walking and bicycling.

Background

The existing highway design of Harrison Street predates Oakland’s freeway system. Harrison was widened to six lanes in the 1930s, and widened again to eight lanes in the 1950s during the construction of the Kaiser Center to accommodate projected traffic growth (filling in part of Lake Merritt in the process, as shown in the image below). However, this traffic never materialized: freeway construction rendered the eight lane highway obsolete, and it has remained half-empty over the past sixty years.

Harrison Street in 1939 (left) and today (right)

(Source: UC Berkeley Earth Sciences & Map Library and City of Oakland)

In 2001/2002, the City revisited the design of Harrison and other streets around Lake Merritt as a part of the Lake Merritt Master Plan. The Master Plan and the subsequent approval of Measure DD set the stage for a multitude of transformative improvements to restore the Lake’s ecosystem, renovate the Lake’s facilities and attractions, and improve access to the Lake. For the most part, Measure DD has been a huge success for livable streets through projects like the 12th Street Bridge, which replaced “the world’s shortest freeway” with a four lane boulevard and plaza (the site of the Warriors’ championship rally), as well as the Lakeshore Avenue road diet, which significantly reduced traffic speeds on the east side of the Lake.

Bad Projections, Bad Design

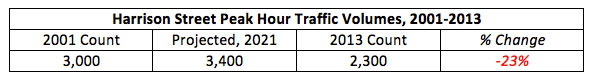

The City’s approach to Harrison Street, however, would prove different than other streets. As a “major downtown roadway link,” the Lake Merritt Master Plan sought to maintain five lanes on Harrison Street based on projected growth in traffic volumes and associated impacts to level of service standards. Sound familiar? Only this time, not only did the projected growth in traffic volumes never materialize; traffic volumes declined. The City counted 3,000 peak hour vehicle trips along Harrison in 2001, and projected these trips would increase to 3,400 trips by 2021*. However, peak hour traffic volumes on Harrison actually decreased by 23 percent to 2,300 trips in 2013, according to the City’s traffic count website. Harrison Street now carries as many vehicles per day (23,900) as Grand Avenue in Adams Point (23,700 vehicles per day), which has four lanes and experiences little congestion, and slightly more than Lakeshore Avenue (21,000 vehicles per day), which has just two through lanes. The City’s five lane design, therefore, will be overbuilt by at least 50 percent for cars that don’t exist.

Considering the location of Harrison Street along Lake Merritt in Downtown Oakland – one of the densest, most transit rich locations in the Bay Area – are car-centric metrics like level of service an appropriate measure of success? A successful design should create a seamless gateway between Downtown and the Lake, one that’s delightful for walking and biking and encourages people to enjoy the location’s beauty. A successful project should also create a convenient connection to BART and Downtown Oakland via 20th Street. To be fair, the Lakeside Green Street project as a whole will incorporate some of these objectives via the revitalization and expansion of Snow Park and the Lakefront, plus a road diet on Lakeside Drive. But such people-focused metrics were barely considered in designing Harrison; in many ways, the new design reinforces Harrison as a barrier for people walking and bicycling.

The Lakeside Green Street project’s approach to Harrison Street is deficient in several ways:

• High-Speed, Highway-Like Condition: Harrison will remain overbuilt for cars, maintaining five lanes, several double-left turns, and a slip lane at Grand Avenue. The design provides no traffic calming on a street where cars routinely exceed 40 mph. It continues to over-allocate space to cars over adding space for walking, biking, and parks.

• High-Stress Bicycle Facilities: Harrison includes unprotected bike lanes sandwiched in between fast-moving cars and parked vehicles, a stressful condition not suitable for most people. The addition of parking doubles the potential sources of conflicts (including car doors and vehicles pulling in and out of spaces). Alternatively, the 10 foot wide walkway bordering the Lake does not have sufficient width for large volumes of people walking and biking to comfortably coexist. For “interested but concerned” riders, there is nowhere to comfortably ride.

• Conflict-Heavy Harrison/Grand Intersection: The preservation of a wide-angle right turn “slip lane” at the Harrison/Grand intersection is problematic on many levels. The wide angle encourages cars to turn at high speeds. The northbound bike lane appears to disappear across the slip lane, creating a barrier for people biking through the intersection to the Harrison/Oakland bike lanes north of 27th Street. The slip lane also reinforces a barrier for pedestrians, who must cross an extra street through the intersection. Today, pedestrians routinely disregard the frustratingly long and unresponsive “Don’t Walk” signal across the slip lane, creating a disorganized and dangerous condition. And let’s not forget that the slip lane cuts through what could have been additional park space.

• Missing Pedestrian Links and Long Crosswalks: It’s surprising that in Downtown Oakland, in 2015, the City of Oakland is still omitting crosswalks from all legs of an intersection. The most inexcusable example of this is at the intersection of Harrison and 21st Street, where pedestrians are not provided with a crosswalk directly linking Cathedral of Christ the Light and Lake Merritt. The crosswalks that were included in the design are very long due to the width of the street.

As a result, the $14 million Lakeside Green Streets project will not provide a transformative reconnection between the Lake and Downtown akin to other successful Measure DD projects like the 12th Street Bridge or Lakeshore Avenue road diet. Instead, the project mostly reinforces, if not exacerbates, existing barriers for walking and biking along Harrison Street.

Frozen in Time

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Lakeside Green Streets project is how little it has changed since it was first conceived in the Lake Merritt Master Plan. In 2002, Uptown was a ghost town after 5pm. Gas was $1.50 a gallon. Today, Uptown has blossomed into a live-work-play destination that’s just starting to achieve its potential. Oaklanders are driving less, while ridership at the 19th Street BART Station is up 60% and commuting by bicycle in Oakland has tripled. Moreover, engineering best practices for bicycling have evolved: protected bike lanes are the gold standard to which any major “green” streets project should include – such as Vancouver’s Burrard/Cornwall intersection.

Over the past decade, the City had several opportunities to update the project’s design. It could have slimmed down the project based on new traffic count information. Or at the very least, it could have modernized its bikeway designs to include protected bike lanes and add in missing crosswalks. Ironically, however, the only noteworthy change to the Harrison Street design occurred in 2013 when the City added curbside parking – a move that will further impair bicycle safety. By and large, the City will build a 13-year-old design on Harrison Street that’s about as cutting edge as a 2002 Pontiac Aztek.

What could have been: Vancouver’s redesigned Burrard/Cornwall intersection incorporates protected bike lanes along a street that carries 50,000 cars per day – double that of Harrison Street in Oakland.

(Source: City of Vancouver)

Next Steps & Lessons Learned

It’s too late to fix the Lakeside Green Streets project: the project is fully designed and scheduled to go to bid by January 2016. Due to federal and state grant funding constraints, the City cannot revise the design’s flaws, including the excessive number of lanes, high speeds, challenging intersections, missing crosswalks, and lack of a continuous bikeway along the Lake. However, there is a sliver of hope for an improved bikeway design: Bike East Bay has lobbied the City to reconsider the inclusion of a protected bike lane, and the City has stated that they would consider its inclusion as a change order once the project was underway. The Measure DD Community Coalition is highly supportive of this change; however, it will require sustained momentum to implement. Individuals supportive of a protected bike lane are encouraged to send comments to:

• Ali Schwarz of the Oakland Public Works Agency at alischwarz@oaklandnet.com

• District 3 Councilmember Lynette Gibson McElhaney at lmcelhaney@oaklandnet.com

• Councilmember At-Large Rebecca Kaplan at atlarge@oaklandnet.com

What can the City learn from this debacle when pursuing future street redesigns?

1. Prioritize the safety and comfort of existing street users over the movement of future traffic volumes. Do not allow guesstimates of future traffic volumes to dictate street designs.

2. Periodically review project designs to ensure consistency with observed vehicle, bicycle, and pedestrian volumes, city policies, and best practice designs.

3. Prioritize walking, biking, and transit use in Downtown Oakland. Strive for all streets to offer safe, convenient, low stress mobility for each mode.

4. Disregard level of service standards and other automobile-centric metrics, as enabled by SB-743.

Downtown Oakland could become a fantastic urban destination that rivals great Downtowns from around the country. But it won’t realize this greatness by repackaging the same cars-over-people strategies of the past 80 years. As the City embarks on a new Downtown Plan, it must learn from its past mistakes to implement a more sustainable, people-focused future.

______________________________________________________

*Lake Merritt Master Plan, Appendix VII-19