(Source: Cruz511)

Unsurprisingly, the widening project is very controversial. Proponents frame the widening as a progressive issue to reduce commute times for working class commuters from Watsonville who cannot afford to live in Santa Cruz. Opponents point out that the benefits of widening highways tend to be temporary as more capacity induces demand for more congestion, and that the widening project is not consistent with local, regional, and state sustainability legislation such as SB-375. Even Caltrans recently acknowledged that widening freeways like Highway 1 does not relieve traffic congestion over the long term, and may not even help in the short term.

The Highway 1 widening project serves as a microcosm of the transportation and land use challenges facing California’s coastal urban areas. Santa Cruz County has made a generation of transportation and land use decisions built around slow growth and preserving its rural spaces and beach town, off-the-beaten-path character. The framework of this vision is now bursting at the seams due to both internal and external economic forces. When evaluating the Highway 1 project, there are no easy solutions – only tough choices that will shape the region’s future.

Santa Cruz’s Housing Crunch

Before evaluating whether widening Highway 1 is the best solution for solving traffic congestion issues, it is necessary to dive into the root causes of this congestion as it relates to Santa Cruz’s housing crisis. By some measures, Santa Cruz is the least affordable city in California, and perhaps the country. A perfect storm of rising demand and limited supply has produced this crisis. Spillover demand from Silicon Valley’s housing shortage has brought more high income buyers and renters to the market, while local employment growth has further increased demand. This increase in housing demand has overwhelmed a constrained housing supply, due to a mix of restrictive zoning, NIMBYs, and rent control. In recent years, the county has added roughly one housing unit for every ten residents.

Median home sales in Santa Cruz now average $800,000, and median rents are around $2,000 per month. Conversely, median household income in the county is just $68,000, and the top five occupations in Santa Cruz pay around $10 an hour. As a result, nearly two-thirds of renters countywide live in unaffordable housing in which their rent is greater than 30 percent of their income. The City also has one of the highest concentrations of homeless residents in the country.

Over the past two decades, a majority of Santa Cruz County’s new housing construction has occurred in the relatively more affordable Watsonville area, where the median price for a home ($480,000) is still high, but about 40 percent lower than Santa Cruz. Consequently, gridlock along Highway 1 between Watsonville and Santa Cruz has increased substantially.

The Highway 1 Widening Project

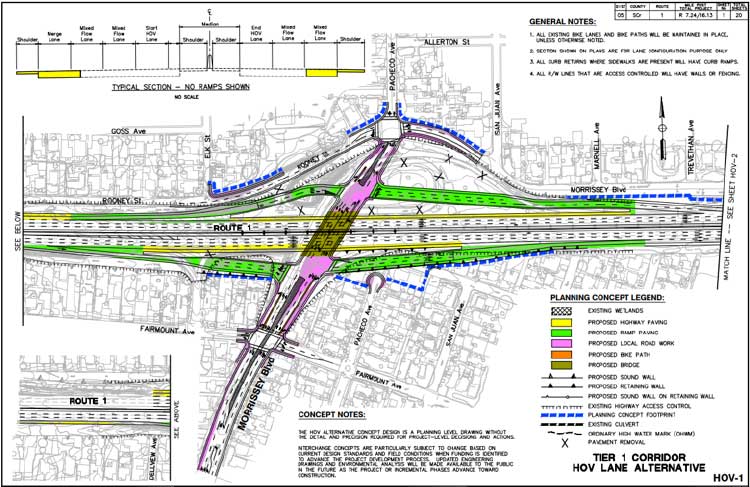

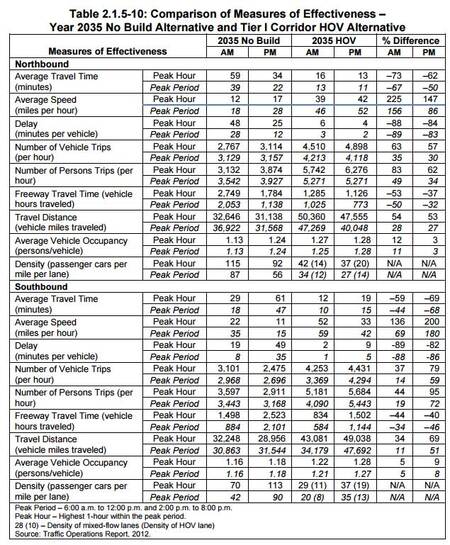

But carpool lanes would also increase vehicle miles traveled (VMT), which is where the project gets problematic. Under SB-375, the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (AMBAG), to which Santa Cruz County is a member, is required to reduce VMT by five percent by 2035 through sustainable land use and transportation strategies. Yet the Highway 1 widening project would increase VMT significantly – SCCRTC projects about a 30 percent increase during the AM and PM peak periods.

The question for Santa Cruz County, therefore, is not how can you cure congestion, but how can you support sustainable growth and give people choices to avoid congestion?

Alternatives to Widening Highway 1

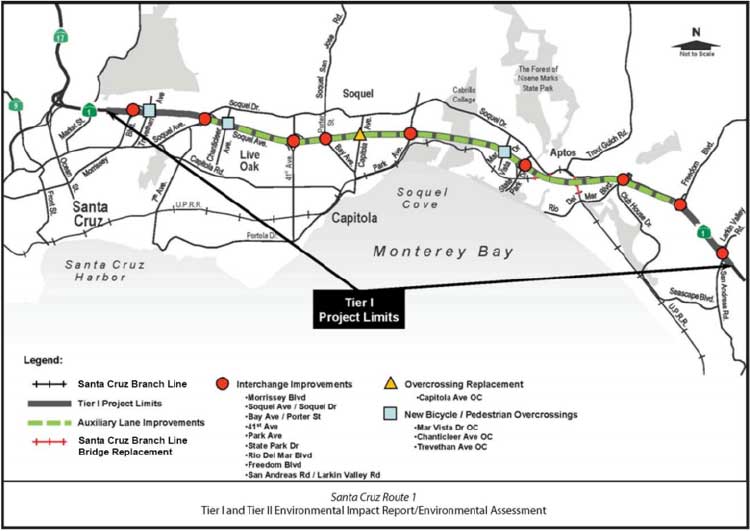

SCCRTC has other mobility options at its disposal beyond widening Highway 1 which support local and statewide sustainability goals. A ‘kitchen sink’ approach of new or expanded transit service, bicycle and pedestrian upgrades, transportation demand management strategies (TDM), and infill-supportive development policies could expand the capacity of person-movement without increasing VMT and greenhouse gas emissions. SCCRTC has evaluated some of these options in isolation, but has not conducted a comprehensive analysis of such alternatives compared to highway expansion.

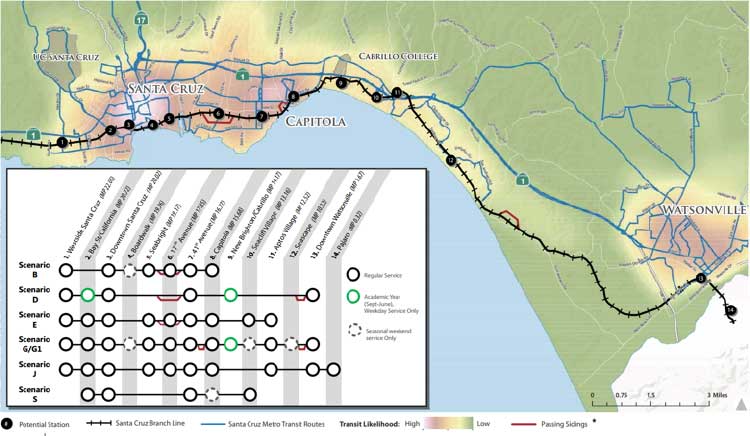

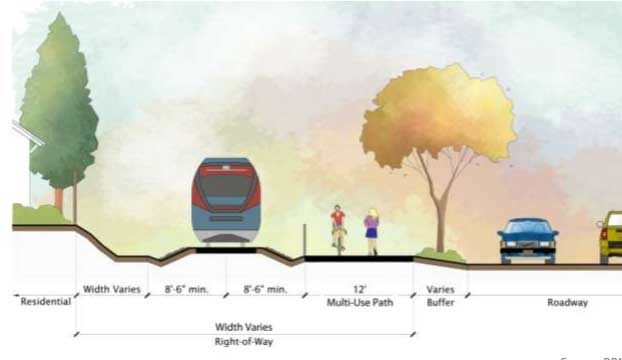

One intriguing option is the introduction of passenger rail service between Santa Cruz and Watsonville. SCCRTC recently completed a feasibility study for passenger rail service along the Santa Cruz Branch Line, a mostly inactive single-track rail corridor that the agency purchased in 2012. Approximately 90,000 people live within one half mile of the rail corridor, which parallels Highway 1. The proposed service could provide a 40 minute trip between Santa Cruz and Watsonville and include about a dozen stations as well as a parallel bicycle and pedestrian trail. An intermodal connection could ultimately be provided at Pajaro Station if Capitol Corridor service is extended to Salinas.

Are There Solutions?

Unfortunately, Santa Cruz County residents will not have the opportunity to participate in a clear conversation and comprehensive evaluation of the tradeoffs between freeway widening and the ‘kitchen sink’ alternative prior to making a decision on the Highway 1 project. In November, Santa Cruz County residents will vote on a transportation sales tax measure, Measure D, to decide the future of the Highway 1 project. The measure would raise $500 million over 30 years, dedicating 30 percent to local road repair, 25 percent to Highway 1 improvements, 20 percent to transit, 17 percent to the coastal rail trail, and eight percent to railroad maintenance and improvements for potential passenger rail service. The Campaign for Sensible Transportation opposes the measure. A similar measure failed in 2004, which dedicated 65 percent of funding to highway widening. While this measure would not fully fund the widening of Highway 1, its passage would provide a voter mandate to move forward with the project.

Ultimately, Santa Cruz’s traffic problems all come back to its housing crisis. Without significant growth in housing in walkable, bikeable, and transit-accessible neighborhoods, any transportation improvement will serve as a temporary band aid. Changing a region’s transportation and land use paradigm is hard work – especially with so much at stake – but in the long run, it may be the only choice for Santa Cruz to be a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous community.

AI-search

AI-search  Email

Email