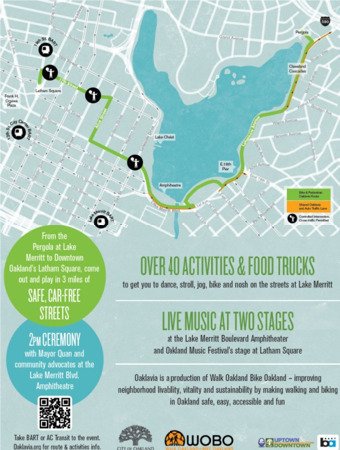

Oakland recently hosted Oaklavia, an open streets event that invites people to walk, bike, dance, play, and socialize in the streets. It’s a terrific, if underappreciated event that both showcases the city’s vibrancy and the potential for stress-free (or low-stress) walking and biking on the city’s streets. At the same time, Oaklavia reinforces the juxtaposition between a safe, enjoyable street environment, and the otherwise inhospitable conditions of many streets around and intersecting Lake Merritt. It begs the question: why can’t biking around Lake Merritt always be safe and welcoming?

Lake Merritt is arguably Oakland’s greatest asset. The tidal lagoon is a beautiful one-of-a-kind environment that has undergone a revitalization in recent years. Oaklavia showcases the lakefront as an enjoyable place to bike for all ages. Bike-friendly streets around the Lake make total sense: not only would they provide access to a valuable recreational amenity, they would also serve as a crucial north-south and east-west links to access BART, Downtown Oakland, and some of the city’s densest neighborhoods.

But bicycle infrastructure around Lake Merritt is half-baked, at best. The trail around Lake Merritt is generally too narrow for bikes (5-6 feet in some places), so bike traffic is generally relegated to the adjacent streets. Some of these streets are better than others: Lakeshore Ave, 1st Ave, and Lake Merritt Blvd are generally good biking streets (although they are still unprotected, parking-adjacent facilities not exactly suitable for bicyclists of all ages). On the other hand, the north and west sides of the Lake are intimidating, if not terrifying environments to bike (and walk across the street). On Lakeside, the northbound bike lane spontaneously ends, and there is no southbound bike lane to be found on Madison. On Harrison, the street is inexplicably 8 lanes wide, designed like a highway from a forgotten era. On Grand, adjacent to Children’s Fairyland, the bike lane feels like an appendage to a street still built to move cars quickly (it’s no wonder few families bike to Fairyland).

Accessing the Lake from other neighborhoods in Oakland is similarly challenging. There are no continuous bike lanes that connect Lake Merritt to any other neighborhoods in the city. From the east, only a pair of sharrows on otherwise fast one-way streets (Foothill and E 15th). From the north, Broadway, Harrison, and 27th come close, but a few weak links limit their utility (hopefully Telegraph Ave will be improved as well). From the west, there are no bike lanes which run across Downtown Oakland, so residents of Downtown or West Oakland must brave four lane speedways. And no link to the Bay Trail currently exists. While Oakland deserves credit for rapidly expanding its bike infrastructure in recent years and has plans to at least partially address many of these gaps, it’s clear that there’s still a long way to go to achieve a street network that prioritizes safety and complete streets.

There are several areas that Oaklavia could improve. For starters, Oaklavia’s limited scope and frequency has largely left it disconnected with Oakland as a whole. Sunday Streets and Ciclavia built their participation around frequent events that took place in widely different areas across the city; in contrast, Oaklavia has largely been a Lake Merritt-specific event that hasn’t really ventured into North, West, or East Oakland (though a smaller event was held jointly with Emeryville earlier this year). The event also isn’t strictly car-free: both this year and last, only about half of the route was opened for people walking and biking; the other sections remained closed and reserved for cars. Yet, given how hard it is to organize these events with very little money, the City and Walk Oakland Bike Oakland still deserve a ton of credit for making it happen.

Oakland is approaching an important moment. The city’s economy is roaring back as a result of spillover from San Francisco’s tech boom. The city is already changing fast, and these changes will accelerate: four specific plans have been or will soon be ratified to reshape development in or around West Oakland, Broadway-Valdez, Lake Merritt BART, and the Oakland Coliseum. The City recently kicked off a Downtown circulation study, is implementing bus rapid transit, and will soon have a bike share network. But with these developments will come increasingly difficult choices: will the status quo of car-first planning be maintained, as it was at Latham Square, or will the city follow its NACTO peers like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City to prioritize safety and complete streets?

Oaklavia plays a huge role in shaping this conversation, let’s keep them coming.